Schrems II - what are the implications for UK and EU data transfers to India?

31 March 2021

Everyone knows the important role India plays in the global digital economy; in fact the Harvard Business Review estimates the digital economy in India “is expected to reach a valuation of $1 trillion dollars (USD) by 2022”. With new Indian legislation on the horizon in the form of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (PDP Bill) and the Schrems II decision from last year we’ve joined forces with our colleagues at J. Sagar Associates to bring you this article setting out the issues you need to consider and sharing some top tips.

What’s the current and proposed data and privacy regulatory framework In India

The current law in India is contained in the Information Technology Act (IT Act) and the Privacy Rules. While these laws protect “personal information” and “sensitive personal data or information”, and apply to body corporates that collect the information directly, they do not specifically apply to State or Government authorities. They also have limited applicability to the indirect recipient of information.

There are some further concerns about the existing laws, including, but not limited to:

- there is no regulator or data protection authority;

- there are no guidelines or regulatory guidance on consent;

- there are no penalties prescribed for non-compliance;

- there are no special requirements prescribed for children/minor’s data;

- they are not applicable to State or Government authorities; and

- there is limited applicability to the indirect recipient of information.

The PDP Bill[1] was introduced to address some of the issues above, as well as the fact that the Supreme Court of India held in 2017 that privacy is a fundamental right protected by Article 21 of the Indian Constitution[2]. This legislation is making its way through the Parliamentary process, currently under consideration by the Joint Parliamentary Committee. It is anticipated it will come into effect at some point in 2021.As with GDPR in the UK and EU, LGPD in Brazil and CCPA in California, it will be a watershed moment for data and privacy laws in India.

It is worth noting that commentators have also raised concerns both about the broad exemptions for Government and State authorities in the current draft of the PDP Bill and the level of surveillance permitted in India. While this may be the case India remains a superpower in the global digital economy and the destination of choice for many when it comes to data processing needs. It is therefore important that companies understand how to lawfully transfer personal data from the UK and EU to India.

Schrems II – so what is all the fuss about?

For those of you familiar with the Schrems II judgment, you will already understand why it is relevant to UK and EU[2] data transfers to India. For those of you less familiar with the case, here is a summary of the facts pertinent to this ruling[4]. (You can also find further detail and comment from Lewis Silkin here[5]).

Maximillian Schrems, an EU national and privacy activist, wanted to stop Facebook transferring his personal data to the US. He believed that notwithstanding whatever protections were put in place (in this case EU-US Privacy Shield) his personal data was not adequately protected against access by government agencies, such as the National Security Agency, Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, as these agencies were granted wide ranging powers in the aftermath of the September 2011 terror attacks. Schrems argued that the US approach to personal data undermined the EU’s high data protection standards. He had already successfully had the Safe Harbor provisions struck down[5], and as he believed his data should not be exported to the US under any other mechanism, he turned his attention to the Privacy Shield and the Model Clauses, also known as the Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). He launched a new claim in the Irish courts challenging the validity of the Privacy Shield and SCCs, and the Irish High Court referred the case to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) for a decision.

In the CJEU’s long and complex judgment, the court found that:

“the requirements of US national security, public interest and law enforcement have primacy, thus condoning interference with the fundamental rights of persons whose data are transferred to that third country”.

In other words because the US governmental agencies have broad powers to demand US companies hand over data, and to review data sets held in the US, this is at odds with the concept of the Privacy Shield, which allows EU data subjects’ data to retain adequate protection when transferred to the US.

This inevitably led to the Privacy Shield being struck down, and while the CJEU was at pains to point out that the SCCs remain a valid mechanism for cross-border transfers of personal data, the CJEU suggested that in order to rely on SCCs controllers (and processors) must undertake (onerous) due diligence to show that the receiving country can guarantee the same protections for EU data subjects. Further, the CJEU also emphasised that supervisory authorities have the authority to audit and review SCCs and stop data transfers where it finds there is no adequate protection afforded by the receiving country.

Several months after this judgment, in November 2020, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) issued two recommendations on international data transfer mechanisms. The first recommendation[7] on “supplementary measures” sets out how to approach Schrems II compliance, with a six step roadmap for data controllers:

It also provides clarity on what the concept of “supplementary measures” might actually mean in practice, with examples of the Technical, Contractual and Organisational “supplementary measures” that controllers (and indeed processors) can take.

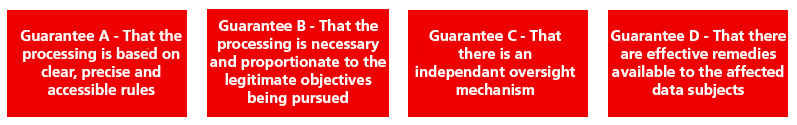

The second recommendation[8] explicitly sets out four European “essential guarantees” which are to be assessed against the surveillance laws of a recipient country of any data to determine whether there is anything in law or practice in that country which might impinge on the effectiveness of the transfer mechanisms (e.g. the SCCs).

The four “essential guarantees” are as follows:

Again…so what?

Why are we talking about a UK or EU citizen’s fight not to have his data transferred from the EU to the US? Data is still flowing freely around the globe so why does this matter? It is clear that the CJEU expects controllers (and processors) to guarantee the same protections for EU (and UK) data subjects as the GDPR affords them in the EU. This means a UK or EU citizen’s data transferred to India must be protected in this way.

Many businesses rely on the SCCs as a mechanism to comply with the GDPR, but following Schrems II this requires due diligence to be undertaken to show that any receiving country, outside the EU or UK which does not have an adequacy decision, can guarantee the high standard of GDPR protections for EU and UK data subjects. The EDPB’s guidance on supplementary measures and essential guarantees (for more see above) will also assist with this assessment.

In India, it is hoped that the PDP Bill will go a long way to address many of the issues and concerns raised and help ensure EU and UK data subjects have the same GDPR level of protection for their data. This new legislation, combined with existing checks, balances and safeguards, considered alongside the EDPB guidance and the new SCCs (when they are eventually finalised) means businesses exporting data to India can do so in a Schrems II/GDPR compliant manner.

Practical top tips for transferring data from UK and EU to India

1. Data mapping, data transfer assessment and contract review

In light of this much publicised judgment, many of you may already have reviewed your contracts and mapped your international data transfers, whether intra-group or via an external data supply chain, to understand where your personal data is going and what mechanisms you are relying on to transfer your personal data from the UK or EU to India.

While you may think you ticked this box when you signed the contract, it is worth revisiting, if you haven’t already done so, as this will help you to assess where any risk may lie and take steps to mitigate it. As more guidance is released and certain supplementary measures become common place, it is likely your data transfer assessment will evolve, and you may need to take further steps to ensure compliance.

Keeping up to date with the UK adequacy decisions, familiarising yourself with the PDP Bill, 2019 and seeking expert legal opinions from local lawyers are all steps you can take now to ensure you don’t fall foul of this judgment.

2. Obtain contractual comfort

Look to supplement your existing warranties in your underlying contract to provide additional commercial and legal comfort. While the SCCs do contain certain assurances from the data importers, as well as obligations to notify, e.g. the controller to processor SCCs require the data importer to warrant compliance with the SCCs and notify the data exporter if it: cannot comply with the SCCs or the data exporter’s instructions; is aware of any local legislation that would prevent it from complying; or receives any requests to disclose personal data to law enforcement authorities unless otherwise prohibited by the local law.

You may want to include contractual provisions that:

- require the data importer to promptly notify when a surveillance request is received;

- give data exporters’ the right to attempt to challenge governmental requests before the data is handed over (where possible);

- rights to require the data importer take additional supplementary measures;

- rights of termination;

- cost allocation where the data exporter is required to suspend transfers;

- allocation of liability; and

- increase liability caps for situations when things do go wrong.

One note of caution, the SCCs differ depending on whether the transfer is controller to processor, as above, or controller to controller, so additional contractual provisions might be required in the latter case.

Finally, remember as the SCCs are currently under review by the Commission, and while they will have a year’s grace period to implement, you can include a contractual mechanism to easily swap in the revised SCCs when they are eventually released.

3. Supplementary measures

Your data mapping, data transfer assessment and contract review will help you almost halfway there with the roadmap steps, and the “essential guarantees” will see you over the halfway line.

4. Essential guarantees

These guarantees will form the basis of any transfer risk assessment that a controller (or processor) may undertake and will be helpful not only for the assessment of how the laws in India stack up against these guarantees but also to demonstrate compliance through a comprehensive audit trail leading to your decision.

5. Article 49 derogations

It has been mooted that for certain ad hoc transfers, it might be a viable option for businesses to rely on other Article 49 GDPR derogations such as explicit consent of the data subject or necessity for compliance with a contract with the data subject. The Article 49 derogations have limited application and reliance on these derogations is unlikely to be a long-term solution for regular data transfers. In practice there has not been much reliance on these derogations since the Schrems II judgment.

What can Indian companies receiving data from EU and UK data exporters do to help?

Many Indian companies are undertaking their own analysis of the current regime and the PDP Bill in light of Schrems II. Commentary focuses on the broad exemptions for Government and State authorities in the PDP Bill and the level of surveillance permitted in India. However, it is important to remember that the Indian legal system has checks and balances, safeguards and remedies already, and the proposed legislation is no different.

The SCCs remain a valid and effective mechanism for cross-border transfers of personal data, and the EDPB recommendations on “supplementary measures” and the “essential guarantees” set out clear steps that can be taken to ensure compliance. The laws of India do not impact the SCCs and it is possible to demonstrate the essential guarantees can be met.

Some companies are choosing to amend their terms and conditions to make them ‘Schrems II friendly’. Such an approach makes it easy for a UK or EU data exporter to sign on the dotted line, safe in the knowledge that the Schrems II issues have been addressed and resolved.

What next?

The repercussions from Schrems II have been felt around the world. Data has not stopped flowing but there has been a flurry of activity mapping, reviewing, amending and assessing data flows and the contractual arrangements that underpin them. The new SCCs, currently in draft form but expected to be finalised in the next few months, have also added to the workload, with those who use them mindful of the one-year transition period they will have to implement the new SCCs when they are finally signed off.[9]

There has also been an increase of collaboration across territories as experts seek to understand local laws, share knowledge and tackle the implications of this judgment together. Both J Sagar Associates and Lewis Silkin have been engaged in helping their clients ensure compliance and future proof existing international data flows. If we can be of any assistance please do contact Probir Roy Chowdhury at J Sagar Associates or Alexander Milner-Smith at Lewis Silkin LLP in the first instance.

- [1] For the text of the PDP Bill click here.

- [2] Justice K.S.Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India [Writ Petition No. 494/2012].

- [3] Please note when we refer to the “EU” in a data transfer context this includes the EEA and Switzerland.

- [4] For a more detailed case history please see Lewis Silkin article “Model clauses for EU-US data transfers under threat in latest Schrems challenge”, July 2019.

- [5] See articles from Lewis Silkin:

- The CJEU’s decision in Schrems II: Privacy Shield invalidated (and SCCs in jeopardy), July 2020.

- EDPB doubles down on Schrems II, July 2020.

- Schrems II - Practical steps on what to do next… , August 2020.

- [6] For further information and to read the original Schrems judgment (Schrems I) click here.

- [7] Recommendations 01/2020 on measures that supplement transfer tools to ensure compliance with the EU level of protection of personal data, EDPB, November 2020.

- [8] Recommendations 02/2020 on the European Essential Guarantees for surveillance measures, EDPB, November 2020.

- [9] The one-year transition period will run from the date of entry into force of the Decision of the European Commission implementing the New SCCs.