With much excitement the EU Parliament’s plenary vote on the EU AI Act (the “Act”) took place on 13 March 2024. The voting was overwhelmingly in favour and the Act is being hailed as the world’s first artificial intelligence legislation aimed at “putting a clear path towards a safe and human-centric development of AI”.

The European Council formally endorsed the final text on 21 May 2024, and then following further linguistic work, the Act was published in the Official Journal of the EU on 12 July 2024 and entered into force 20 days after publication, on 1 August 2024, with a staggered implementation allowing different provisions to come in over a three-year period (see below for more detail).

So, whilst there is still a little way to go before the various provisions enter into force, it is important to understand the impact it might have on your organisation and the steps you can take now in order to prepare.

Who does it apply to?

In summary, the Act applies to “providers”, “importers”, “distributors” and “deployers” (both public and private) of “AI systems” which are placed on the EU market or which affect those located in the EU; i.e. in a similar way to GDPR it purports to have a wide jurisdictional “reach”. Brussels, as ever, is keen to promote the “Brussels effect”.

AI systems

There has been much debate through the Act’s passage as to what an AI system means. The Act has now aligned its definition with the OECD’s definition, i.e.

“An AI system is a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.”

The Act makes it clear we are not talking about automation, rather the key distinguishing factor is the AI system’s capability to infer something; basic and very commonly used automation tools are therefore out of scope.

Key role definitions

The Act defines what it means by “providers”, “importers”, “distributors” and “deployers”. Note there we will need to see how these definitions are interpreted via guidance, commentary and case law but for now the Act sets out that:

- “Provider” means “a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body that develops an AI system or a general purpose AI model or that has an AI system or a general purpose AI model developed and places them on the market or puts the system into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge”.

Think: Open AI, Google and other well known AI leaders, but do be aware that many unexpected players will be inadvertently caught by this definition (and some mere “Deployers” will be caught as “Providers” depending on how they implement AI Systems).

- “Importer’” means “any natural or legal person located or established in the Union that places on the market an AI system that bears the name or trademark of a natural or legal person established outside the Union”.

- “Distributor” means “any natural or legal person in the supply chain, other than the provider or the importer that makes an AI system available on the Union market without affecting its properties”.

The boundary between Importer and Distributor is grey and we will need to see who falls into each camp but Think: Third party intermediaries selling Provider systems into the EU.

- “Deployer” means “any natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body using an AI system under its authority except where the AI system is used in the course of a personal non-professional activity”.

Think: The User (be it a business or an individual) of an AI system; but for those of you, like one of the authors, that uses ChatGPT to create bed time stories for their children do note the non-professional activity exemption (i.e. no need for privacy notices for your children!).

It is important to understand your role in order to understand the obligations that will apply as there are different levels of obligation depending on your role; and we talk more below about other key steps you can take with regard to the Act.

The Act does not in general apply to providers of free and open-source models (some exemptions apply e.g. systemic general purpose AI (“GPAI”) models even if open source will be subject to regulation), AI systems used for national security, military, or defence, or research, development and prototyping activities (prior to release on the EU market).

When does the EU AI Act come into force?

The Act was published in the Official Journal of the European Union on 12 July 2024, and came into force after 20 days, on 1 August 2024. There is then a staggered implementation allowing different provisions to come in over a three-year period depending on the type of AI system (see below for more information on these systems) in question:

- 2 February 2025 - 6 months after coming into force the bans on prohibited practices will apply;

- 2 May 2025 - 9 months after the codes of practice should be ready;

- 2 August 2025 - 12 months after the obligations for general purpose AI including governance will apply and penalties will come into force;

- 2 August 2026 - 24 months after the Act is broadly fully applicable, including obligations for many high risk systems (those listed in Annex III - see below for more information as to what type of systems this covers); and

- 2 August 2027 - 36 months after the obligations for other high risk systems (those defined in Annex I - see below for more information as to what type of systems this covers) will apply.

See below for more detail on what these terms, e.g. “prohibited practices” and “high risk systems” mean, but in summary this is a long run in before the Act is fully in force, during which time a lot might change in the world of AI.

Expedited compliance – the AI Pact?

Recognising the timescales involved, the fast pace of the technological developments and the increase in public awareness and usage of AI systems, the European Commission wants something to plug the gap. The so-called AI Pact is designed to do this.

It is “a scheme that will foster early implementation of the measures foreseen by the AI Act”. The commitments will be pledges to work towards compliance with the Act (even before the time frame above comes into being), including details about how the obligations are being met. The Commission will publish these pledges to “provide visibility, increase credibility, and build additional trust in the technologies developed by companies taking part in the Pact”.

In November 2023, the Commission launched a call for interest for organisations willing to get actively involved in the AI Pact. On 25 September 2024, the EU Commission brought together key industry stakeholders to celebrate the first signatories of the pledges. The organisations involved have committed to at least three core actions, namely

- “Adopting an AI governance strategy to foster the uptake of AI in the organisation and work towards future compliance with the AI Act

- Identifying and mapping AI systems likely to be categorised as high-risk under the AI Act

- Promoting AI awareness and literacy among staff, ensuring ethical and responsible AI development”

It is currently a watch this space situation to see how many companies actually make these pledges as they can be signed at any point up until the EU AI Act becomes fully applicable. While these pledges are not legally binding, nor do they impose any legal obligations on the signatories, might deployer customers start forcing provider vendors to sign up to the AI Pact as part of commercial negotiations? Might it become a due diligence AI procurement question? Might it become a provider marketing tool i.e. “We are already compliant with the EU AI Act via the AI Pact”?

Types of AI and different risk and obligations

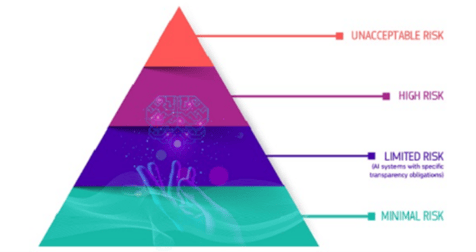

The Act takes a risk-based approach, identifying four categories of risk (i.e. the higher the risk the greater the obligation), as well as the more recently included specific obligations placed on Providers of GPAI models.

The different categories of risk are:

- Unacceptable risk (prohibited)– AI systems “considered a threat to people and will be banned”.

These systems are prohibited and so must be phased out, at the latest, six months after the Act comes into force (2 February 2025).

Examples include AI systems that pose a significant risk to fundamental rights, safety or health, e.g. social credit scoring systems, emotion-recognition systems using biometric data in the workplace and education institutions (exceptions apply), untargeted scraping of facial images for facial recognition, behavioural manipulation and circumvention of free will (note that recital 29 expressly states that this does not cover advertising), exploitation of vulnerabilities of persons, e.g. age, disability, biometric categorisation of natural persons to deduce or infer their race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs or sexual orientation, certain specific predictive policing applications and real-time remote biometric identification in public by law enforcement (exceptions apply).

- High risk – AI systems “that negatively affect safety or fundamental rights will be considered high risk”.

This is where the majority of time, resource and focus will be needed as most of the text of the Act addresses these systems and this is where the most stringent “day-to-day” obligations apply (outside the outright ban of prohibited AI systems). It is essential to understand your role in order to understand which obligations apply, e.g. are you a Provider (Articles 16 – 22) or a Deployer (Article 26)? (see below for a summary of these different roles).

High risk systems are split into two –

- the list in Annex I (i.e. AI systems considered to be high-risk because they are covered by certain EU harmonization legislation (an AI system in this Annex will be considered high-risk when 1) it is intended to be used as a safety component of a product, or the AI system is itself a product covered by the EU harmonization legislation; and 2) the product or system has to undergo a third-party conformity assessment under the EU harmonization legislation)); and

- the list in Annex III of high systems which are “high risk” as classified as such by the Act.

Examples of high risk systems in Annex III include:

- certain non-banned biometric identification systems (excluding biometric systems that confirm who a person says they claim to be);

- certain critical infrastructure systems;

- AI systems intended to be used in relation to education and vocational training; and

- AI systems intended to be used in relation to access to and enjoyment of essential private and public services.

In addition, and very importantly as this will likely touch on every company with employees in the EU, Annex III makes clear that AI systems intended to be used in many employment contexts (amongst other things - recruitment or selection of individuals or to monitor and evaluation performance of employees and or their behaviour) are considered high risk.

Do note that Providers who believe their systems sit outside these high-risk parameters can (because for example they only perform “a narrow procedural task” or “improve the result of a previously completed human activity”) must document why they believe the high risk rules do not apply. We will see how many Providers take up this exemption as it will be subject to significant scrutiny from both the relevant authorities and Deployers.

- Limited risk – “refers to the risks associated with lack of transparency in AI usage”.

AI systems that are not high-risk but pose transparency risks will be subject to specific transparency requirements under the AI Act.

Providers must ensure that users are aware that they are interacting with a machine, that AI-generated content is identifiable, that solutions are effective, interoperable, robust and reliable, while deployers must ensure that AI-generated text published with the purpose to inform the public on matters of public interest must be labelled as artificially generated and AI-generated audio and video content constituting deep fakes must also be labelled as artificially generated. Examples of AI systems in this category include chatbots, text generators and audio and video content generators.

- Minimal risk – “the AI Act allows the free use of minimal-risk AI”.

There are no additional requirements mandated by the Act. Examples of AI systems in this category are AI-enabled video games, spam filters, online shopping recommendations, weather forecasting algorithms, language translation tools, grammar checking tools and automated meeting schedulers.

Providers of General purpose AI (“GPAI”) models

In addition to the above categories of “risk” assessed AI systems, the Acts imposes specific obligations on providers of generative AI models on which general purpose AI systems, like ChatGPT, are based. Providers are required to: perform fundamental rights impact assessments and conformity assessments; implement risk management and quality management systems to continually assess and mitigate systemic risks; inform individuals when they interact with AI (e.g. AI content must be labelled and detectable); and test and monitor for accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity.

Where GPAI models are considered systemic (i.e. when the cumulative amount of computing power used for a model’s training is greater than 10>25 floating point operations per second) providers will be subject to additional requirements to assess and mitigate risks, report serious incidents, conduct state-of-the-art tests and model evaluations, ensure cybersecurity, provide information on the energy consumption of these models and engage with the European AI Office (see below for more information about this newly formed body) to draw up codes of conduct.

Differing roles, differing obligations?

Understanding your role in relation to the EU AI Act is crucial as there are different obligations. This is probably best illustrated by looking at the key provider and deployer obligations for high-risk systems where we believe the main compliance focus under the EU AI Act will fall:

| High Risk AI systems | |

| Providers | Deployers |

|

|

Enforcement

What are the relevant Institutions?

There are myriad different institutions, some old some new, that will take an interest in enforcing the Act.

The AI Office was formally established on 21 February 2024 , sitting within the Commission, to monitor the effective implementation and compliance of GPAI model providers, as well as in summary being responsible for production of codes of practice (in conjunction with other relevant parties). The codes of practice, due to be published by 2 May 2025, will be essential tools to help bridge the gap between the high-level regulatory principles and the day to day operations of AI developers and users. The codes will add substance to the regulation by providing actionable practical steps, assisting with identifying and managing risk and ensuring compliance where codes are followed, while supporting innovation by having a clear framework balancing new systems with ethical and safety considerations.

In addition to the EU AI Office, the European Artificial Intelligence Board (analogous to the European Data Protection Board) was established on 1 August 2024, and comprises high-level representatives of competent national supervisory authorities, the European Data Protection Supervisor, and the European Commission. Its role is to facilitate a smooth, effective, and harmonised implementation of the Act, to co-ordinate between national authorities and to issue recommendations and opinions.

Member State authorities (and it will not necessarily be current data regulators but may be a combination of regulators) will be responsible for local enforcement and indeed the Act allows for individuals to lodge an infringement complaint with a national competent authority.

With so many different bodies involved expect either perfect harmony or potentially contradictory and confusing guidance, decisions and commentary.

What are the penalties for non-compliance?

The penalties set out in the Act are as follows:

- Non-compliance with prohibited AI practices, up to 7% of global annual turnover or €35 million.

- Non-compliance with various other obligations under the Act, up to 3% of global annual turnover or €15 million.

- Supplying incorrect information to authorities, up to 1% of global annual turnover or €7.5 million.

It will also be important to follow the progress of the AI Liability Directive, which aims to introduce rules specific to damages caused by AI systems to “ensure that victims of harm caused by AI technology can access reparation”. The current proposal introduces the “presumption of causality”, which means victims will not have to “explain in detail how the damage was caused by a certain fault or omission” and when dealing with high risk AI systems they will have access to evidence from suppliers and companies. This is an attempt to level the playing field for individuals who have suffered harm as having to meet the burden of proof under the existing fault-based liability regime could make it “excessively difficult if not impossible for a victim”.

There is also the revised Product Liability Directive to consider. It updates the EU strict product liability regime and will “apply to claims against the manufacturer for damage caused by defective products; material losses due to loss of life, damage to health or property and data loss”; It is limited to claims made by individuals but it is clear why those working in the AI space will need to be aware of the changes and how they affect their business.

More familiar data and privacy claims under the GDPR have to be considered as well (i.e. many AI use cases involve voluminous personal data processed under GDPR) – as such the rights of individuals have to be considered in the round and there are multiple routes to enforcement and avenues claims that will be important to understand.

So what should you be doing now?

There is a lot to think about and whether you who already have AI systems in place or you are considering the use of new AI systems, in very broad summary and just as initial starting point thoughts, you need to think about the following: [note this is from the point of view of a Deployer – Providers et al will have different considerations].

1. AI Systems Audit: What AI systems do we use or are we planning to use?

2. EU AI Act Applicability Audit:

- Does the Act apply to any of these?

- What risk categories apply? [EU AI Act Applicability Audit]

- What is our role under the Act? Are we a Provider? Are we a Deployer etc?

3. Leverage off Providers:

- What due diligence have we done on Providers specifically re their compliance in relation to the Act?

- How can they help us with our own compliance with the Act?

4. Data Governance (current systems and new processes):

- What is the best governance method for us to cover all our obligations under the Act? (i.e. do we need to consider a mixture of procurement due diligence on Providers with our own internal DPIA process running through all our obligations?)

- Think about data & privacy and procurement compliance processes we already have in place that can take some of the slack

- How are we going to repeat this again and again to ensure continued compliance?

- Do we need, if we do not have one already, a multi stakeholder AI Governance committee?

- Should we put in place AI audit systems to ensure such continuing compliance?

These are just ideas and every business will have its own approach but if initially a business is thinking about AI Governance Considerations, doing an AI Systems Audit and an EU AI Act Applicability Audit, considering how best to Leverage off Providers and then thinking what current compliance systems it can redeploy/re-tool to assist – it will be on the right track.

Jurisdiction agnosticism?

This article has been focused on the EU AI Act, which although wide in jurisdictional scope, is just an EU piece of legislation. There are other approaches around the world, for instance see our article comparing the UK vs EU vs US.

For international organisations a decision needs to be made – are you going to have a jurisdiction by jurisdiction approach to AI compliance and governance? Or will you attempt to create a jurisdiction agnostic approach (i.e. creating a compliance and governance structure that takes the best (or worst as the case may be) of the legislation around the world to create a high-level compliance and governance structure that can flex as and when legislation changes, emerges, disintegrates?

If you would like to know more about the EU AI Act, please do get in touch with your usual Lewis Silkin contact.